Ælia Media is a participatory art project for Bologna by Pablo Helguera for the First International Award for Participatory Art. Consisting of a nomadic cultural journalism institute and broadcast center in Bologna, and an alternative arts multimedia channel online, the project functions in two capacities:

- A training ground for active and aspiring cultural producers

- A temporary broadcast program in a variety of media (video, print, radio, web) with a focus on engagement through live participation and online social networks.

The project was launched as a alternative arts journalism school in May of 2011 in Villa delle Rose, Bologna, and the radio station Ælia Media was launched at Piazza Puntoni on October 15, 2011, the same day of a massive protest in Rome and of global protests against economic greed.

At a time in Italy where media is dominated primarily by right wing interests, Ælia Media responds to an important tradition of alternative radio in Bologna, connected to the student movement of 1977. The live transmisssions are done in collaboration with the three main remaining alternative radio stations in Bologna, Radio Cittá Fujiko, Radio Cittá del Capo and Raio Kairós.

Ælia Media’s mission is:

- To provide a physical, nomadic, and virtual space where dialogue around culture, and the analysis of social and political issues can be debated;

- To raise the visibility of the contemporary arts in Bologna;

- To support curators, artists, performers, and other experimental artists in showcasing their works;

- To give an opportunity to emerging artists, art producers, and individuals new to the field to test out their ideas to a larger audience;

- To provide concrete skills for media production to those interested in

- showcasing their work;

- To develop programming that may activate a dialogue between the art community and social activists and remain as an archive documenting the cultural life of the city;

- To offer possibilities to the local community to continue this project as a sustainable initiative.

- To present its creative process with absolute transparency, to gain the confidence and support of the Bolognese community, while at the same time instigating reflection and response through provocative programming.

Workshop with Miran Mohar from the Slovenian collective IRWIN, Villa delle Rose, Bologna, October 2011

Project Narrative

introduction

Political and Social Background

The Emilia Romagna region has a long and significant history of social activism, grassroots and progressive thinking. Ever since the the 19th Century, the Emiliano-Romagnoli have shown a strong commitment in creating support systems for the disadvantaged, which many times have crossed political lines (ranging from the Societá di Mutuo Soccorso in the 1880s[1] and other centers run by Catholic charities to today’s social centers for the elderly in Bologna[2]).

Similarly, as a region that holds the oldest university in the world, the area has shown equal awareness and progressive thinking in the field of education, most notably through the creation of the Reggio Emilia approach, a revolutionary early education practice started in 1945. The Reggio system emphasizes creativity, the empowerment of the individual in their own education, and a decentralized decision-making process that is greatly mediated through creativity and conviviality in a visually stimulating environment.

The historical inclination of the region toward collectivism and equality manifested after World War II when the city of Bologna became the leading center for the Italian left, a role which continues to this day and has given Bologna the nickname “La Rossa” (the red one).

Bologna also played a central role in the history of Italian communism. According to writer Edmondo Berselli, the kind of communism of the Bolognese is an orthodox version, “a practical thing, impregnated with work and the construction of peace”[3] which emphasizes pragmatic solutions and which came from the “conviction of the professional bourgeoisie that […]the bourgeois and the communist worlds needed to find a modus vivendi. It is not so difficult.[4]”

Bologna’s role as a center for the left as well as a university town led to it becoming the main center for the student protests in Italy in 1977, “a strange movement by strange students” which revolved around working class concerns[5].

|

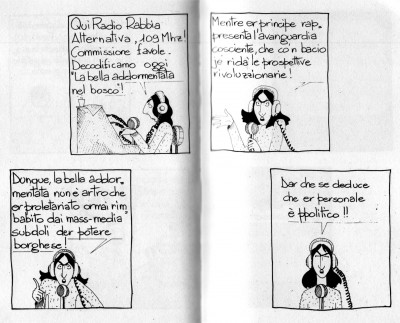

The student movement led the birth of the independent radio and independent media movement. Stations like Radio Popolare, Radio Cittá Futura, and Radio Onda Rossa emerged during this period. Of these, the most influential was Radio Alice, an independent/guerrilla radio station initiated in 1976, one of the first and most prominent platforms of communication for the young left and inspired the emergence of other similar networks in Italy. The cultural/artistic faction of the student left, known as the “indiani metropolitani” (metropolitan indians), sought to take on a critique of mass media with a kind of theatrical, satirical and creative approach, with a energy and imagination that has been linked to the Situationists and the Futurists. One of the famous slogans of this group was “La Fantasia Distruggera’ il potere ed una risata vi seppelira” (“fantasy will destroy power and a laughter will bury you”).[6] The collectively written mission of Radio Alice was to “propose to give voice to delirium, to the irrational, to the everyday, to the infinitely subjective, to the extemporaneous, to the paradoxical.[7]” The role of irony in the new left movements of 1977 is seen as critical since it marked a break with the ‘68 generation and the humorless political class holding power in Italy at the time.[8]

This emergence of independent critical and satirical spirit in the Emiliana region is not an isolated event: the region has a rich tradition of satirical journalism since the 1920s with magazines such as Corriere Emiliano, Bertoldo, and Candido (this last one a monarchist publication although also satirical, in which the famous writer Giovanino Guareschi contributed to the form). The practice continues to this day with the writings of journalists like Michele Serra.

The radicalization of the left through the student movement came to a head with the brief overtaking of the city of Bologna by student groups during three days in 1977 and the response by the socialist government itself, which resulted in the death of a student, Francesco Lorusso. The same day, police arrived to Radio Alice and shot down its operations definitely.

The events of that year remain deeply engrained in the minds of the Bolognese. After the violence and social tensions of the 1977 student movement, the city would be shaken again shortly thereafter with the terrorist attack on the Bologna train station in 1980 by neo-fascist groups. This event remains a painful and traumatic chapter in the history of the city. The fact that the clock of the Bologna station was intentionally left marking the hour in which the terrorist act occurred becomes a powerful symbol of how the city has difficulty moving on from those events.[9] While it is hard to accurately assess the cultural impact of these incidents, it is generally seen as a turning point in the history of the city. A local artist remarked, in one of the interviews I conducted, “Bologna died in 1980”[10].

Another significant, if perhaps not comparable event that altered the liberal Bolognese’s perception of themselves as a progressive city was the historical electoral loss of the left to a non-communist candidate in June 1999 (The Italian Communist party dissolved in 1991 and its leader, Achille Ochetto, transformed his party into a progressive left wing party declaring that the era of Eurocommunism was over).

The success of the center-right in the liberal bastion of Italy was a particularly painful symbol that underscores the political direction that Italy has taken since the mandate of media mogul Silvio Berlusconi.

According to Fausto Anderlini, sociologist and director of the Metropolitan Research Center of Bologna, the return of the right to the city and the re-establishment of the influence of the church manifested in subtle ways, such as the repositioning of the statue of St. Petronio in-between the two towers of Bologna, the very urban axis of the city. “The symbolism of this repositioning was not lost amongst Bolognans”.[11] Curator Mili Romano has further remarked: “the statue of St. Petronio, positioned at the end of the commercially-developed Via Rizzoli appears to be giving his blessing to the new shopping culture of the city.”[12]

|

The previously mentioned events in Bologna and the Emilia Romagna region have punctuated what is regarded as a process of gradual weakening of the left in Italy. The reconfiguration of social and economic factors in Europe over the last twenty years have presented a challenge for the left as it tries to adapt its platform to the new realities of the country. An example, in cities like Bologna, is the increased immigration from North Africa and the Middle East, one of the highest in Europe. While the left has vacillated to adopt a strong position on the issue, the right has instead taken this phenomenon as an opportunity to criminalize these groups (even if most immigrants earnestly seek to become lawful and productive members of Italian society) and blame them for the economic and social instability of the country, producing anti-immigration laws which further isolate and ostracize them.[13]

|

From my various conversations, interviews, and research it is clear that there is currently a soul-searching moment amongst the Bolognese left, of trying to understand the current state of affairs, trying to find new models to reinvigorate progressive thinking in the region and make the ideals of the left appealing again to the new demographic of voters in the region.

To aggravate matters, quoting Anderlini again, “The left self-destructed under its own self-satire”: that is, the left has further fragmented itself by oddly turning its criticism mainly onto itself and using its own satiric tradition to self-immolate in public.

Somehow, that old orthodox and pragmatic version of communism described by Berselli no longer appears viable in a country with such unpredictable future; instead, individualism, neoliberalism and separatism have emerged and taken control with the full support of the central government and the media.

The art scene

The art world in Bologna appears to represent a microcosm of the larger social and political identity issues that are currently at play in the region.

Bologna has a history of alternative art spaces which served as room for experimentation and dialogue amongst contemporary artists, as well as venues for emerging artists in the Bologna art schools. The proliferation of some of these spaces in the early 90s is closely linked to the clandestine occupation or squatting of unused buildings. Such was the origins of organizations such as TPO (Teatro Polivalente Occupato) and Link.

According to Link’s founder, Silvia Fanti, Link functioned as an organization “where we didn’t make a distinction between producers and audience.”[14] The constituents of this space often presented new artworks or films, collaborated and attended a variety of activities that ranged from exhibitions to screenings, discussions and other programs.

Toward the beginning of the following decade, however, these spaces underwent a transition that caused them to either close or become even more established and abandoning their original alternative or experimental edge (Link continues to exist although under a different group of producers and mainly functioning as a music club). The transition may have had to do with the changing situation with squats in Bologna (which became less viable) and the moving on of the original founders of these spaces. However, in contrast to what usually happens in other cities with a fluid art scene, these alternative spaces were not replaced by other projects or venues.

Today, the situation of alternative spaces in Bologna is dire. In my research to find spaces for the production and presentation of contemporary and alternative art forms, most of my interlocutors were hard-pressed. The Neon Campobase Gallery, where I presented a collaborative performance during my stay in Bologna and which is considered by most as the most enduring and well-known of alternative galleries, has informally announced that it will close in February of 2011. In group discussions and one to one conversations I held with various performance artists and theater groups, there is a consensus that there are far too few venues and opportunities to present their work in the city, which results in many giving up their production or moving to another city to continue working.

Most importantly and also from my conversations with local producers I got the sense that, aside from the reduced options of exhibition or performance venues, there are no clear replacements to the alternative venues of the 90s where the exchange and discussion about art took place; no drop-in spaces that currently facilitate a conversation or dialogue about common issues.

Sociologist Ray Oldenburg in the 90s proposed the notion that all communities need a “third place” (a location that is an alternative to work or home) in order to thrive. Third places are usually the local pub, the café or other social space where people who think alike gather to have unstructured interactions. The art community in Bologna has lost its third places, and with the exception of a handful of locations where a few book presentations happen (such Bar La Linea) there does not appear to be a permanent place that would allow for social interaction.

Some artists I spoke to, such as Sissi (Daniela Olivieri) and others, are based in Bologna but don’t see the city as a place where they should invest their energies or even exhibit their work. Those who produce valuable work in Bologna, such as Elisa del Prete, who directs the artist residency Nosadella Due, feel that their work is precarious and feel isolated in their efforts.

Opportunities

In the previous section I have outlined what, to the best of my abilities and with the limited knowledge that my personal interactions and research about Bologna have afforded me, I consider significant issues and challenges facing the region. I now would like to highlight what I perceive as the opportunities and potentialities in proposing a participatory project in the city.

Bologna continues to be a comparatively rich city with some of the most attractive urban landscapes amongst major cities in Italy. The fact that the city is not overwhelmed by the tourist economy (such as it happens to Rome, Venice or Florence) allows for its local life to breathe a more independent air and not be subjected to the outside visitor. The university continues to attract a vast student population, which brings a variety of skills and interests. While venues are lacking, there are many artists and cultural producers willing and interested to be a part of something larger.

The generation who participated in the student demonstrations of 1977 are still present and wish to share their experiences, as shown by the publications that have emerged chronicling these years. This generation has also been responsible for jumpstarting other means of autonomous communication, most notably with the appearance in 2002 of TV Orfeo, and the network it created, Telestreet. Founded with the idea to use the redundant frequencies that large broadcasters do not use in their transmission, TV Orfeo became an independent/pirate form of television with a short field of transmission (around 200 meters usually) but with the ability to bring together small communities.

|

This kind of TV production, although humble, could be seen as a spontaneous citizen response to the current overtaking of the media by the Italian Government (given that the head of state is also the owner of most of the entire country’s telecommunications).

The pioneering efforts of a few individuals, such as the project Cuore di Pietra and others by curator Mili Romano, have shown that there is great potential for public art in Bologna, both in piazzas and in the periphery of the city. Romano’s projects have reached out to disenfranchised communities through collaborative and pedagogical approaches.

Another hopeful experience during my stay in Bologna was with the interaction of the members of La Pillola, a group of young professionals of diverse disciplines seeking to redefine the working environment. Through this redefinition, La Pillola also explores new ways of collaborating and becoming cultural producers. The pro-active, pragmatic and constructive approach of this organization marks an exciting mode of working for a new generation.

|

Finally, in my visit to the schools of Reggio-Emilia, I found a story that stood in stark contrast to the one in Bologna. The school system of the Reggio schools is proliferating, nourishing an ethnically diverse student body, and nonprofit organizations like Re Mida, which takes recycling as a creative medium promoting green practices and sustainability, has helped Reggio become one of the leading cities of Italy in recycling.

In my present proposal I submit the view that the philosophy behind the Reggio Emilia approach, the collective pragmatism that has characterized the region, the satirical angle of its journalism, and the socially-engaged activism and participatory nature of its independent radio and television

can all be drawn upon to create an expanded critical platform of cultural production that would again create a space where, as Fanti mentioned, there is no distinction between the audience and the producer.

Ælia Media

[ a new idiom] requires spectators who play the role of active interpreters, who develop their own translation in order to appropriate the ‘story’ and make it their own story. An emancipated community is a community of narrators and translators.

Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator

Don’t hate the media— be the media

Jello Biafra

Summary

Ælia Media consists in the creation of a nomadic cultural journalism institute and broadcast center, as an alternative arts multimedia channel. The project would function in two capacities: one, as a training ground for currently active and aspiring cultural producers, and second, as a temporary broadcast program in a variety of media (video, radio, print, and web) with a primary emphasis on user-generated content (consumer-generated media) using live participation methods as well as online social networks. The webpage of Aelia Media will function as a multi-media news center where program streaming will be available and ongoing debates will take place.

The project will derive its strategies from processes of learning, self-organization, and media production that have local roots but with a contemporary emphasis and outlook. The “Aelia Media Corporation” will try to be a cabinet of curiosities of cultural journalism, searching for the extraordinary in the ordinary, rediscovering the wealth of cultural production in Bologna, and juxtaposing opinions on specific issues, tying them with larger issues internationally.

The presentation and broadcasting of the programs will be conducted from a specially designed kiosk to be placed in a public plaza in Bologna with substantial presence of student population. The idea behind this kiosk is to 1. Provide visibility of the project in the city; 2. Establish a location in the form of a “third place”. In addition, the kiosk would occasionally “travel” to other locations in the city to reach other communities or to bring attention to particular issues in the city.

Rationale

The public program as location. The art community in Bologna currently lacks a space where to discuss and debate. In the words of sociologist Ray Oldenburg, it lacks a “third place” — that is, a social surrounding where more informal exchanges can take place. In previous years, the art organizations mentioned before apparently served this purpose, but today it is hard to find a location that would fulfill this purpose. While this project will provide an opportunity for artists groups to present and discuss their projects, Ælia Media would not seek to become a physical alternative space where art is physically exhibited — as the prospect to administer and program such location would supersede the possibilities of this grant and would be more of a curatorial task. However, Ælia Media would function as a temporary third place by virtue of its presence in plazas and the regularity of its programming. Bologna already has plenty of bars and cafes — desirable hangouts for artists and non-artists alike. What is missing is a focus of conversation, which can be achieved by this project, which would position its temporary kiosk amongst spaces that already have the café or bar infrastructure[16].

Art community involvement. After my various interactions with local curators and artists, I concluded that the idea of bringing an artist from outside to present a public art project in Bologna with substantial (and official) government support and public funds, has the potential to further alienate the local art community, who (rightly or wrongly) may see an investment of resources passing them by instead of being invested in them. I thus want to propose a project that, while remaining open to participation to a general audience, would make an effort to involve the local art community as key players. These local producers are, in my view, the ones who can provide the true content of the project by sharing their interests, showcasing their projects in descriptive formats, and reaching out to the larger public, some of which in turn may have a chance to participate.

In terms of the benefit for the art community, I believe that providing art agents with the means and tools of communication can allow them to spread their ideas and initiatives more effectively, while at the same time offering them a community environment to exchange ideas. The project at the same time will rely on those artists who have links to the region and already have production experience to conduct workshops as part of the program (one such organization is Alterazioni Video).

Narration and Translation. Content for this project will emerge from a series of workshops and debates on the cultural history of Bologna and the current issues faced today locally and also internationally. Participants will be asked to learn to “translate” the issues of the past into the present and learn narrative strategies to address them.

Multi-tiered participatory structure. Much art that proclaims itself as participatory proposes models of exchange that are little more than small alterations to the rituals of the traditional passive viewer in an art exhibition. Such models may include attending a meeting or a class, joining a workshop, contributing a small object toward an installation, etc. While some of these approaches may be appropriate for their respective contexts, I believe that every art project with social integrity must at the very least show some awareness about the difference between “symbolic” or “token” participation versus deeper engagement. Moreover, I believe that an art project should also admit the reality that the large range of public that may be exposed to it will also display an equal range of desires to engage, as well as the possibility that an enticed viewer that interacts at a symbolic level and feels rewarded by the experience may want to engage further at a deeper level. For this reason, in order to become truly functional in a public realm, a participatory process in my view should ideally strive to be such that the participant is rewarded by the level of engagement (in time and effort) that he/she is willing to invest in the exchange. A breakdown of the levels of participation is provided in the action plan.

Content of the programs. Programming may include a) description and discussion of current and future art projects in the city; b) debates on cultural policy; c) general discussions on contemporary art; d) discussions about the role of the media; d) interviews and guest interlocutors from the local art scene in Bologna; e) news and other curiosity items.

Media and the cultural moment. This initiative emerges as a response to a social and cultural need in the city, but also as a statement about the state of media in Italy. Television in Italy responds to conservative and commercial interests to an extreme, even amongst the general standards of mass media in the developed world. While small, this intends to be a small gesture toward criticality and autonomy, seeking to draw from the legacy of independent media while also trying to bring it to the next generation of social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, etc.)

Sustainability. This proposal is conceived with the objective to create a sustainable platform that could be undertaken by members of this art community – or other local Bologna residents with similar interests. While not a central condition for the success of the project, I believe that a key objective must be to ensure that collective participation can translate into ownership, or, equally valid, the realization that a similar project could emerge in response to this one. While the kiosk may not be preserved, other elements such as the website/blog may have a chance to continue its life after the end of the project.

Documentation. The project will place special emphasis on the gathering, editing and organizing of the material that will result from the experience (transcripts, videos, transmissions, sound recordings, performance scripts, etc) both with the objective to give longevity and visibility to the project but also to create a resource for younger artists about what was produced.

Physical structure

The goal of the physical kiosk is to exist as a transparent “cabinet of curiosities” where passersby can see “news in the making” in the fashion of street-level newsrooms that are made available for people to view their real-time broadcasts. The kiosk would be conceived as a collapsible structure made out of transparent material for viewing (such as plastic windows used for greenhouse structures).

The structure of the kiosk is inspired in cabinets of curiosities located in the Museo di Palazzo Poggi of the University of Bologna, which display the original collection of Ulysse Aldrovandi, the founder of Natural History. The structure simulates, to a degree, the various towers of the city (which historically were created to establish status) and most importantly would make a direct reference to the political subtext of the movements of the monument of St. Petronio. If in a city like Bologna the moving of a monument is a political gesture, then the sensible answer is to create a project that behaves as well as a nomadic monument — to free expression.

In sum, while the proposal is to secure a piazza (preferably Piazza Verdi) as the “base” for this kiosk, the idea of it being relatively easy to transport is both logistical and political — the kiosk could travel to other locations in the city to reach other “participants”, and to draw attention to significant historical locations in the city.

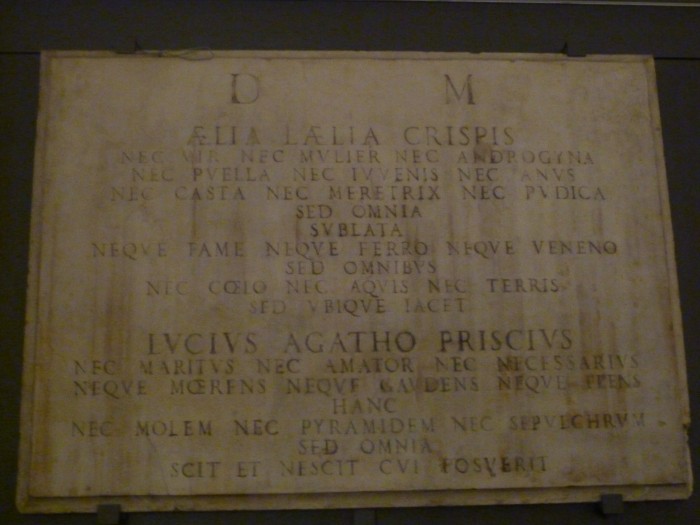

AELIA LAELIA CRISPIS

|

The name of the proposed project makes a reference to a famous cryptic epigraph that has been known for four centuries as “the stone of Bologna” or “the enigma of Bologna”. The stone that bears this name, despite its historical notoriety, is located in a seldom-visited gallery in the Museo Civico Medievale di Bologna, often hidden by a projection screen used for lectures. Although it is regarded amongst scholars as a “famous” stone, the piece and its history are barely known amongst the general public.

The tombstone reads as follows:

D. M.

AELIA LAELIA CRISPIS

nec vir nec mulier nec androgyna

nec puella nec iuvenis nec anus

nec casta nec meretrix nec pudica

sed omnia

sublata

neque fame neque ferro neque veleno

sed omnibus

nec coelo nec aquis nec terris

sed ubique iacet

LUCIUS AGATHO PRISCUS

nec maritus nec amator nec necessarius

neque moerens neque gaudiens neque flens

hanc

nec molem nec pyramidem nec sepulchrum

sed omnia

scit et nescit cui posuerit

The text in English would translate approximately thus:

For the Manes[17]

Aelia Lelia Crispis

Not a man, nor a woman, nor hermaphrodite

Nor girl nor young nor old

Nor caste, nor a prostitute, nor modest

But all of the above,

Killed

Not by hunger not by the sword nor by poison

But by all of the above;

Not in air, not in sea, nor in land,

But everywhere she lays

Lucio Agatone Prisco

Not husband, nor lover nor relative

Not sad nor happy nor mourning

This

Not stone, nor pyramid, nor tomb

But all of the above

Knows and doesn’t know to whom is dedicated.

This epigraph was first made reference to in 1567 by a senator named Achille Volta. Volta reportedly had the ancient inscription redone in a more contemporary marble stone, which is the version that survives today. We know this information because the stone is accompanied by a smaller inscription that describes this fact (what could be described today as the first interpretive exhibition label).

In addition, the various accounts about this stone in the XVIth century add three more verses that did not make it into the extant stone inscription:

hoc est sepulchrum intus cadaver non habens

hoc est cadaver sepulchrum extra non habens

sed cadaver idem est sepulchrum sibi

This is a tomb without a corpse,

This is a corpse which is not contained by a tomb;

but the corpse and the tomb are one and the same.

The text, which seemingly refers to a dead loved one, is regarded as a riddle in the hermetic and emblematic tradition of XVIth century Bologna. Ever since that time, the stone of Bologna has remained as an object of curiosity and reflection by generations of erudites, writers and historians, including Bolognese naturalist Ulysse Aldrovandi and eminent foreign visitors such as Sir Walter Scott, Gèrard de Nerval and Carl Jung, all of which wrote about this stone and tried to decode its mystery. At different times the stone inscription has been interpreted as describing alchemy, music, abortion, the relationship between body and soul, time and shadow, love, all the things of the world— and the list goes on. [18]

**

The project of “Aelia Media” takes the enigma of the stone of Bologna as a symbolic departure point for a variety of reasons. The spirit in which the riddle was created denotes ambiguity, playfulness, and knowledge — three qualities that have been historically characteristic of Bolognese culture, up to and including the countercultural left-wing movement of the 1970s. An analogy between the 1970s title “Radio Alice” and the proposed “Aelia Media” is also intended, but by reaching to the past for the female name (Aelia) and the medium to the present (the more comprehensive contemporary digital communications term, “Media”). Furthermore, the phrase of the Proletarian Youth Circles movement, “a laughter that will bury you all”, is intended to also be given an extension through this tombstone that contains, ultimately, the implicit laughter of the riddle inventor. The project seeks to trace a subtle line between the intellectual Bolognese spirit that created the famous riddle and the rebellious spirit of Radio Alice, which proposed, as previously mentioned, “to give voice to delirium, to the irrational, to the everyday, to the infinitely subjective, to the extemporaneous, to the paradoxical.”

The intention to link the counter-cultural movement of the 70s to the ancestral history of Bologna is more than an arbitrary decision: in the analysis of the legacy of the activist legacy of the recent past, I find it important to take a longer historical view of the social and political scope of a society, in order to gather a certain distance from the immediate past and thus resist its easy mythologizing.

Last but not least, the project intends, in a modest way, to offer yet one more reading of the stone, this time from the present time and from the current cultural moment in which it is being read. What this exact reading could yield will only be determined after the end of this project, if it in fact became a reality. My sense would be that, whatever the outcome, it may point toward the idea that Aelia Laelia Crispis may be the very city of Bologna in the current time, and the narrative of the epigraph may be found to express its myriad contradictions, and shed some light on what was it exactly that died in 1980 (as the art student said) how that death of the city lives within its inhabitants (in terms of the last line of the inscription “ the corpse and the tomb are one and the same”) and how a city that encompasses both vitality and stillness could hopefully draw from both to construct its new identity and its meaning. And if it can be done, I believe, it has to be done with self-determination, proactive gestures, and a dose of irony. It is in a small way in which this project hopes to open the door toward these explorations.

[1] A detailed description of the range of cooperatives, unions, charity organizations and other similar societies is provided by Amletto Ragazzi in “Dalla Vecchia Reggio al Mondo Nuovo: Economia, Società e Primo Socialismo a Reggio Emilia, 1886-1901” Edizioni Diabasis, 2010

[2] See “Aspects of the Cooperative Home Care for the Elderly in Bologna, Italy”(chapter 6) , in Lucille Rosengarten’s “Social work in Geriatric Home Care”, Psychology Press, 2000

[3] Edmono Berselli, “Quel Gran Pezzo Dell’Emilia,” Mondadori, 2004, p. 18.

[4] Ibid. p. 19

[5] Diego Benecchi, ed. “Le Parole dei Luogi Bologna ‘77”, Edizione Sigem, Modena, 2009

[6] It has been suggested that Umberto Eco’s attack to the critique of laughter, which is the central subject of the novel The Name of the Rose (1980), is a reference in support to this student slogan (Eco is professor at the University of Bologna).

[7] Benedecchi, Ibid, p. 37

[8] A key paper that analyses this phenomenon in depth is by Patrick Gun Cuninghame, “A Laughter that Will Bury You All”: Irony as Protest and Language as Struggle in the Italian 1977 Movement, IRSH 52 (Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis), 2007

[9] Margherita Bianchini, “Le 10:25 del 2 agosto 1980: quando il tempo si è fermato”, from “101 Storie su Bologna”, Newton Compton Editori, 2010

[10] Interview with artist Fedra Boscaro, September 2010.

[11] Conversation with Fausto Anderlini, September 2010

[12] Conversation with Mili Romano, September 2010

[13] See Peter Williams, “The World’s Worst Immigration Laws,” in Foreign Policy, April 29, 2010. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/04/29/the_world_s_worst_immigration_laws

[14] Interview with Silvia Fanti, September, 2010

[15] It should be noted that the project will be conducted in Italian with some partial translation into an English version on the blog for international visitors. I am proficient in reading and understanding Italian and have a middle proficiency in communication in that language.

[16] In a recent essay, I have argued for the notion that true alternativity in contemporary art today lies primarily not in the construction of a physical location, but in the use of time in the shape of the public program (Helguera, “The Public Program As an Alternative Space”, in “Playing by the Rules: Alternative Thinking/Alternative Spaces”, Apexart, New York, 2010)

[17] D.M. stands for “Dis Manibus”, which is a common Roman inscription referring to the Manes, deities that represented the souls of lost loved ones.

[18] A comprehensive collection of all the texts relating to the stone of Bologna can be found in the book “Aelia Laelia: Il mistero della Pietra di Bologna”, edited by Nicola Muschitiello, Società Editrice Il Mulino, Bologna, 2000.